The University of Florida Returns to the Envision Resilience Challenge with Historic Preservation

The University of Florida's Historic Preservation team during a site visit to Providence, Rhode Island. Linda Stevenson, Tess Flemma, Hisham Khafaji, Emma Ramseyer, Rae Shropshire, Tyler Smith and Craig Steckelberg (not pictured)By Jolie Jaycobs

This year, the Envision Resilience Challenge brought together twelve teams of students, studying architecture, sustainable design, historic preservation and more, from six universities. The Envision Resilience Narragansett Bay Challenge welcomed back two teams from last year's challenge, Northeastern University and the University of Florida, while also welcoming new participants from the Rhode Island School of Design, Roger Williams University, Syracuse University, and the University of Rhode Island.

Linda Stevenson, Professor of Historic Preservation at the University of Florida.As the month-long showcase of this year's Narragansett Bay design proposals at WaterFire Arts Center comes to a close, we are looking back on the past two years with the University of Florida. University of Florida’s 2021 design studio was an impressive undergraduate team led by Jeff Carney of the College of Design, Construction and Planning. Jeff, an architect and urban designer, returned for the 2022 design studio and along with him, the Challenge welcomed Cynthia Barnett and a small-but-mighty team of three from the College of Journalism and Communications, as well as Linda Stevenson and a dynamic group from the University of Florida’s historic preservation program.

I spoke with Linda Stevenson to learn a little more about what drew the UF Historic Preservation program to Envision Resilience, and the unique goals they worked to achieve this year. Here’s a sneak peek into our conversation.

JJ: The University of Florida is connected to Nantucket through the Preservation Institute Nantucket, which sounds like a field school for your historic resiliency and preservation programs. Beyond that, what drew you to be a part of the Envision Resilience Challenge this year?

LS: Well I really think [climate change] is the issue of our time. You know, it's interesting for me as an older faculty member because a lot of this really bad stuff is probably not going to happen until I’m dead. But I know your generation and my granddaughter's generation is going to be facing serious, serious issues. So for me it's a real mission to contribute where we can and also to make sure that people understand that our historic communities are resilient in so many ways… So I just really wanted to speak up for these resources, especially in New England which has a huge amount of these historic resources. And personally, I love Rhode Island. Coastal Rhode Island is one of my favorite places in America.

JJ: Can you tell me a little bit more about the goals of your studio in relation to this Challenge?

LS: We found a very interesting neighborhood that was perched by the Port of Providence. The Port is interesting because it's a major American port that is definitely threatened by sea level rise. By 2100 most of it is going to be inundated.

“Different groups come to the United States, they move to different communities, they bring their own culture and heritage and they respond to their environment in their own way. All of those responses and stories are equally important and valid to present and to share. ”

There is this community sitting up on a bluff overlooking the port…and what we found is that it had this great collection of historic residential, commercial and industrial buildings from the 1880s to the 1970s. But the core of the residential neighborhood was really developed from the 1890s to the 1940s. So it had this great collection of historic buildings that had not really yet been surveyed on the State or National Register of Historic Places in Rhode Island.

So we thought to ourselves, ‘hmm here we have this great community, a great collection of buildings. It's not officially recognized or even documented yet. And as people flee the flood waters it's ripe for gentrification…The community itself is sort of at the mid to lower socio-economic end of the scale. Property values are lower than other neighboring communities, which means developers are going to be eyeing this community, and there aren't protections in place. That means they can come in, tear everything down and build a bunch of new stuff to increase density. So we decided that this was kind of the perfect storm. Our goal was ultimately to determine how we could leverage the historic assets that are there in such a way as to protect and celebrate that community's character. But also [we wanted to] achieve goals of increasing density for housing, affordable housing and commercial redevelopment along the commercial corridors.

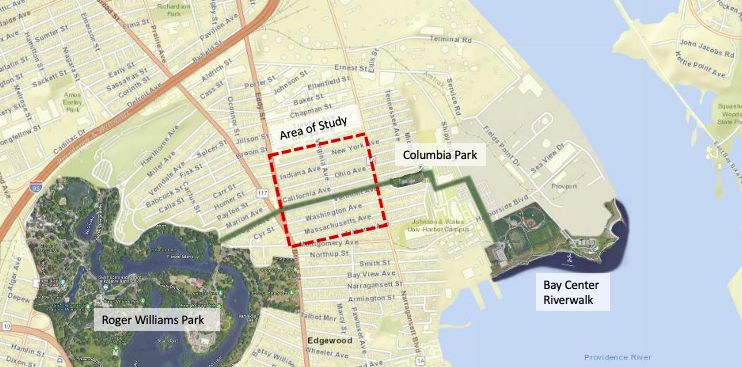

Map view of The University of Florida’s study area in Washington Park, Providence, RIJJ: Can you speak more to what historic preservation means for marginalized or lower income communities?

LS: Yes, I think the key here is that there's been a real soul searching in the preservation movement in the last decade. We started out as a fairly elitist movement… We still haven't done a great job of telling all the stories and acknowledging the different ways that communities change over time. Different groups come to the United States, they move to different communities, they bring their own culture and heritage and they respond to their environment in their own way. All of those responses and stories are equally important and valid to present and to share. I think one of the challenges with preservation now is to figure out ways to successfully rehabilitate buildings—but not to the point where the original occupants can no longer afford to live in their community.

Linda and some of her students with Carl Destephano of SWAPOne of the things we discovered is that Providence is particularly sensitive to this issue, which is what I really loved about this community. They have an organization [that we got to work with] called SWAP (Stop Wasting Abandoned Properties). It was founded in the early ‘70s and it was a time when the urban flight out of the cities to the suburbs was high. So there were a lot of abandoned properties sitting around. This organization was founded with the goal of trying to address housing needs: rehabilitating the buildings while maintaining a level of affordability for people. It's been incredibly successful and it's still working today! They are very sensitive and thoughtful about the kind of work they do with the aim of helping people find housing.

The other thing that Providence has is the Providence Revolving Fund. The concept of the revolving fund is you get financing together, you rehab a few buildings, you then sell or lease the buildings to replenish your funds and then move onto the next project. They do a ton of community outreach too, by helping people with [rent money, food], they have small home repair loans…and they do a tremendous amount of community work in addition to their main mission which is rehabbing these historic places.

JJ: I think a lot of the time historic preservation and climate change resiliency or adaptation are pitted against each other. Sometimes they seem contradictory. Could you speak to how those things can be tied together or can work together?

LS: To me they are undoubtedly tied together. I am not in the camp that thinks that they are opposed at all. I think preservation is part of the bigger issue of resilience. When you think about all that embodied carbon in our buildings, if you can rehab them and reuse them that's so much better. And I think part of the issue probably is that old school preservation really focuses on material authenticity…There was a great report done in 2012 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Green Lab. They did a study on historic windows and lifecycle costing, and that's the key the life cycle costing, so…what they found was that if you properly maintain your window and use some very simple methods like storm windows in the wintertime, different kinds of shades on the windows, awnings and similar strategies, you can cost effectively improve your energy use markedly compared to ripping out and putting in new windows and having to amortize the cost over 30 or 40 years….I really think we should view historic preservation as a key part of sustainable development.

On the resiliency side, one of the challenges before was that we didn't want to move a building if you could help it because the context, the setting of the building was really important also. And the other issue was how high can you elevate your building above flood waters before you lose the historic character of a community. And I have to tell you in the last three years I think that whole idea has been turned upside down on its head.

The National Park Service has done a lot of work on this, and the NPS is the one who issues the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Historic Preservation and that's kind of the guideline that we all abide by. Long story short the National Parks Service did this amazing study about elevating buildings and how you flood proof historic buildings. They produced their own document now - so in addition to the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rebuilding Historic Buildings, there's also a Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Resiliency and Flood Adaptation, and there's another Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Sustainability and Historic Preservation - so there's three standards now that i think have really caught up to the main issues.

JJ: What did your team get out of taking this challenge on?

LS: Well, I think the hope is that the conversation continues and that the skills and knowledge base that the students gained from participating in this project will apply to our entire Florida coastline and any other place they work. I really think it's an educational experience, a fantastic opportunity, and I'm really excited that we get to participate.

JJ: Great, Thanks Linda! I really appreciate you giving some context about yourself and the group that you are bringing to envision resilience. Thanks for taking some time!

This conversation enlightened me to the many intricacies of the relationship between climate resiliency and historic preservation. In my assessment, Nantucket, towns in the Narragansett Bay, and all historic towns along the coast, should feel confident to pursue creative solutions that will progress climate resiliency while still staying true to historic roots. The Envision Resilience team is fortunate to have had such thoughtful groups, like the University of Florida, working on this challenge and designing a resilient future.

About the author: Jolie grew up on Nantucket Island. She graduated from Haverford College in 2020 with a B.A. in Environmental Studies. Since then she has worked for a few nonprofits in environmental advocacy and education. She now works in faculty support at the Harvard Business School. When she visits the island Jolie still loves to spend time exploring Nantucket’s beautiful natural places through biking, running and sailing.